UPDATE: I don't want to add another post to the phenomena, but if you do want to see the latest comment I've put on one of the blogs of Bell's detractors, see comment 20 below. I'm happy to talk about this more in the comments if anyone wishes.

First of all, come on. We are none of us perfect, but we can do better than this blogger. Based on the trailer we ought to have questions, not condemnations. Let's stay out of the pre-emptive anathemas and ism-hunting and hear the brother out.

Secondly, Bell's teaser is provocative, no doubt, but none of the theological questions asked in it are new. In fact they are important enough that they have been discussed and debated with varied results within Christianity for centuries. Bell may be worthy of critique, but we will have to see. And "worthy of critique" is a far cry from "servant of Satan" (a charge made explicit in the first run of the blog post and then amended to be merely implicit).

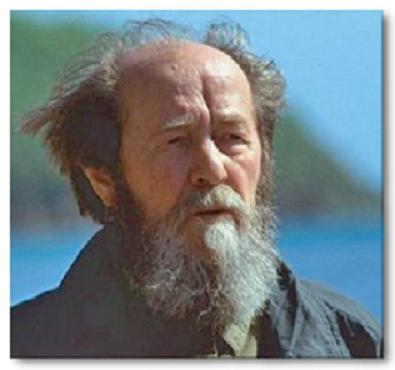

Thirdly, this reminds me so much of what I've been researching in Karl Barth the last couple weeks it is uncanny. Readers may recall the letter I posted a little while back in which Barth was responding to a request from Christianity Today (put to him through a friend) to defend himself against theological suspicions. What were they? You guessed it: He had been labeled a "universalist". I'll re-excerpt the letter below (and give something of Barth's actual, theological reply below that), so you can see how Barth responded to this blogger's ilk in his day:

Dear Dr. Bromiley,To be sure, I think this debate is closer to home for Bell and so he will probably be best to carefully and gracefully enter the fray - but I wouldn't blame him for finding some resonance with Barth's feeling at this point!

Please excuse me and please try to understand that I cannot and will not answer the questions these people put. To do so in the time requested would in any case be impossible for me. The claims of work in my last semester as an academic teacher (preparation of lectures and seminars, doctoral dissertations, etc.) are too great. But even if I had the time and strength I would not enter into a discussion of the questions proposed.

Such a discussion would have to rest on the primary presupposition that those who ask the questions have read, learned, and pondered the many things I have already said and written about these matters. They have obviously not done this, but have ignored the many hundreds of pages in the C.D. where they might at least have found out — not necessarily under the headings of history, universalism, etc. — where I really stand and do not stand. From that point they could have gone on to pose further questions.

I sincerely respect the seriousness with which a man like Berkouwer studies me and then makes his criticisms. I can then answer him in detail. But I cannot respect the questions of these people from Christianity Today, for they do not focus on the reasons for my statements but on certain foolishly drawn deductions from them. Their questions are thus superficial.

The decisive point, however, is this. The second presupposition of a fruitful discussion between them and me would have to be that we are able to talk on a common plane. But these people have already had their so-called orthodoxy for a long time. They are closed to anything else, they will cling to it at all costs, and they can adopt toward me only the role of prosecuting attorneys, trying to establish whether what I represent agrees or disagrees with their orthodoxy, in which I for my part have no interest! None of their questions leaves me with the impression that they want to seek with me the truth that is greater than us all. They take the stance of those who happily possess it already and who hope to enhance their happiness by succeeding in proving to themselves and the world that I do not share this happiness.

Indeed they have long since decided and publicly proclaimed that I am a heretic, possibly (van Til) the worst heretic of all time. So be it! But they should not expect me to take the trouble to give them the satisfaction of offering explanations which they will simply use to confirm the judgment they have already passed on me.

Dear Dr. Bromiley, you will no doubt remember what I said in the preface to CD IV/ 2 in the words of an eighteenth-century poem on those who eat up men. The continuation of the poem is as follows: “… for there is no true love where one man eats another.”

These fundamentalists want to eat me up. They have not yet come to a “better mind and attitude” as I once hoped. I can thus give them neither an angry nor a gentle answer but instead no answer at all.

With friendly greetings,

Yours,

Karl Barth

P.S. I ask you to convey what I have said in a suitable manner to the people at Christianity Today.

Now, of course, Barth did answer the questions about his seeming "universalism", and he did so in print. The question was put to him best by G.C. Berkouwer, in a book called The Triumph of Grace. Here is something of Barth's reply:

‘If I am in a sense understood by its clever and faithful author, yet in the last resort cannot think that I am genuinely understood for all his care and honesty, this is connected with the fact that he tries to understand me under this title....

Grace is undoubtedly an apt and profound and at the right point necessary paraphrase of the name Jesus,’ but ‘the statement needed is so central and powerful ... it is better not to paraphrase the name of Jesus, but to name it’ lest we become concerned with a principle rather than a living person at precisely the place where that person matters most (Church Dogmatics IV/3.1, 173). God is love, but ‘love’ is not God.

Furthermore, 'universalism' is an -ism that doesn't get us very far. You have to say more. Barth didn't go in for a lot of -isms and neither should we. In fact, he quite famously and aptly remarked: "I don’t believe in universalism, but I do believe in Jesus Christ, the reconciler of all."

Undoubtedly this is one of the more difficult questions in theology. I am not sure if I admire Bell's boldness or find his promotional teaser a bit flippant. Regardless, this is not an open and shut theological issue - it deserves careful consideration and gracious dialogue, and I imagine that is what he'd hope for. Please let's not reduce everything to principles, label everyone by those principles, and then proceed as if we are protectors of a point of view rather than persons in communion with faith seeking understanding.

Undoubtedly this is one of the more difficult questions in theology. I am not sure if I admire Bell's boldness or find his promotional teaser a bit flippant. Regardless, this is not an open and shut theological issue - it deserves careful consideration and gracious dialogue, and I imagine that is what he'd hope for. Please let's not reduce everything to principles, label everyone by those principles, and then proceed as if we are protectors of a point of view rather than persons in communion with faith seeking understanding.

At this point Bell raises questions, but does not merit condemnations. If anything, the main question we might ask is why it isn't called "Jesus is Victor"? But we aren't going to be legalistic about book titles. The least one can do is read the book before leveling a full-bodied critique (let alone anything worse).

It is probably more indicative of my interests than anything else, but I come back to two passages in the Bible more often than any others: Genesis 1-3 and Matthew 18. In the latter passage we have what I think is one of the most important pieces of practical and ideological ecclesiology going - straight from the mouth of Jesus.

It is probably more indicative of my interests than anything else, but I come back to two passages in the Bible more often than any others: Genesis 1-3 and Matthew 18. In the latter passage we have what I think is one of the most important pieces of practical and ideological ecclesiology going - straight from the mouth of Jesus.

Of course, what one does when it is one's particular local church which is refusing the ministry of reconciliation is a whole other story. But in that case one is better off confronting that church with their own gospels in hand than retreating to the safe confines of a meaninglessly tolerant society and firing potshots at the Church from a supposed place of moral superiority. That would be the way Pharisees treated pagans and tax collectors, not Jesus. And today I think there are as many Pharisees outside the church as in it.

Of course, what one does when it is one's particular local church which is refusing the ministry of reconciliation is a whole other story. But in that case one is better off confronting that church with their own gospels in hand than retreating to the safe confines of a meaninglessly tolerant society and firing potshots at the Church from a supposed place of moral superiority. That would be the way Pharisees treated pagans and tax collectors, not Jesus. And today I think there are as many Pharisees outside the church as in it.