A new story of origins, or of birth, is in Christ's flesh given to all. Hence, it is from inside Israel's covenantal story, rather than from some general humanism or cosmopolitanism, that Christ in bringing Israel's story to crescendo reintegrates the differences of creation ...

The Babel story tells of the confusion of language and identity that results from the refusal to hear YHWH's call and the resultant inability to speak rightly or in light of that call. The other story is that of the Holy Spirit (Acts 2) in which one reads of the Pentecostal reimagining and reordering of language and identity on the basis of a renewed auditory capacity...

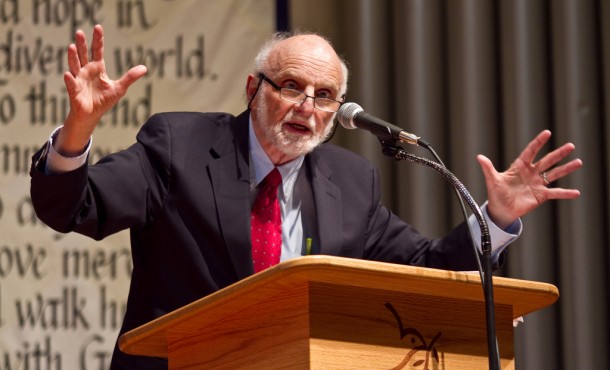

|

| Walter Brueggemann |

The issue is not simply scattering ... [because] scattering may be either an act of punishment or the plan of salvation. Nor is the issue oneness ..., which may be the purpose of God or an act of resistance. Either unity or scatteredness has the possibility of being either obedient or disobedient. The issue is whether the world shall be organized for God's purpose of joy, delight, freedom, doxology, and caring. Such a world must partake of the unity God wills and the scattering God envisions. Any one-dimensional understanding of scattering denies God's vision for unity responsive to him. Any one-dimensional view of unity denies God's intent for the whole world as peopled by his many different peoples (Genesis, 100-101).

It is as though they [the One and the Many] were drawn into an all-powerful center that had built into it the beginnings of the lines that go out from it and that gathers them all together (PG 91.1081B-C)...[For Maximus,] Scripture repositions bodies inside the social space of Christ's Jewish flesh and [draws them] into the socio-theological space of his body, [so that] one is drawn into a new body politic."

In true Christian community, then, concludes Carter, God is "making the many one with himself but without in the act of unifying them confusing what is distinctive about the many."

- J. Kameron Carter, Race: A Theological Account, pp. 347, 351, 364-366

To read the rest of this series summing up Carter's book, follow the index below. Thanks for reading along. I'd be happy to discuss any comments you might have so feel free to leave some.