Tuesday, December 23, 2014

22 December: A True Story

Last night out of nowhere I was confronted by a teenager and two younger kids at my door, caroling. The boy looked right at me as he sang, the girl showed signs she might break out and dance, the older one stood free of self-consciousness. When I asked if they were from our neighbourhood, to my surprise they named another, much less affluent, one. When I gestured to see if I could find something like the figgy pudding they had asked for, to my chagrin they showed no interest in a reward and turned cheerily away. Normally I find caroling very awkward, but this one will stick with me; this time felt like gospel.

Monday, December 22, 2014

Scot McKnight's A Community Called Atonement

'The processes that generate church growth, internal strength, and vitality in a religious marketplace also internally homogenize and externally divide people. Conversely, the processes intended to promote the inclusion of different peoples also tend to weaken the internal identity, strength, and vitality of volunteer organizations.'

That's a quote from Michael Emerson and Christian Smith's Divided by Faith, which Scot McKnight utilizes to introduce his book: A Community Called Atonement. The context of the quote is the observation that 90% of American churches contain 90% people of the same colour.

McKnight suggests that those 'processes' have much to do with the way churches 'package' the 'gospel' (p. 5). In this book McKnight does not fully address our church-dynamics but aims to bring a full-bodied approach to understanding the gospel so churches can think straight.

One way to talk about how we understand the gospel is to talk about 'atonement', or, the question of how the gospel works' (p. 1). Any attempt to do this must be done with a certain 'postmodern humility,' McKnight believes, because we can only reach into God's side of the story by use of metaphor, and because we can only speak of our side from within our limited contexts. Since no biblical or traditional atonement metaphor appears intent on supplying a comprehensive or exclusive account of the gospel of Christ, instead of looking for a 'winner' McKnight makes the not-so-modest attempt to hold them all together (ch. 11).

The attempt is an interesting one, and McKnight does it well. He begins in part one with Jesus, humanity as the image (or Eikon) of God, with sin and eternity, and with church and Christian practice--the idea being that the gospel is all about these things. In part two he examines the different 'moments' of the atonement--from Christmas to Cross to Easter to Pentecost--arguing that none says all that needs to be said, and giving a compelling picture of the gospel and its intended effects.

In part three McKnight examines the different ways the gospel story was narrated early on--first in the implications of Jesus himself (who framed the events of passion week in terms of Passover and liberation), then in the explanations of the apostle Paul (which serve up a well-told account of today's debate about 'justification'), and then in the reflections of early church theologians Irenaeus and Athanasius (who spoke of it in terms of God's 'recapitulation' of dead humanity).

Rather than put them in competition, after a short synopsis of atonement theories, McKnight coins a phrase which he thinks sums them up: The accomplishment of the gospel is 'identification for incorporation' (107). Whether we're talking about Jesus ransoming from death, satisfying his own judgment of sin, substituting as a punishment for sin, representing us before God, recapitulating us to our proper life, or even providing a moral example of self-giving love, it all adds up to identification for incorporation:

'Jesus became what we are so that we could become what he is.'

As McKnight explains it, Jesus' death on the cross (and perhaps descent into hell) are the extent of God with us; his identification 'all the way down' (110). Furthermore (to use a Barthian turn of phrase), Jesus' resurrection and sending of the Spirit are the extent of us with God; an incorporation into God's own life which goes all the way into eternity and all the way into our lives here on earth.

Normally a book on the atonement might end here, except that McKnight wants to stress the point about incorporation; about our side; about atonement as an act of God which has personal and social implications in the here and now. These implications are not subsidiary byproducts but constitutive elements of the work of the gospel (126). That's not to say that the effect of the gospel depends upon our enactment of it, but that there is a 'potential performative reciprocity in the redemptive work of God' (29).

In other words, the gospel gives birth to a new humanity--on earth as in heaven--complete with new fellowship, just praxis, and mission for a whole world. Thus the book's title: implying that atonement does not end at a divine declaration of our 'savedness' but enfolds us as participants in ours and creation's redemption.

This is all well and good--and I do recommend the book highly--but I was left with a couple practical concerns. The first is that forgiveness is considered synonymous with reconciliation (30). If you think about the difference between forgiving someone and healing a relationship with them, you will recognize how that conflation of terms might collapse the participatory action of this newfound atonement community in all kinds of unhelpful ways.

The second concern can be seen if we go back to that first quote above. If attentiveness to our gospel 'processes' are important, I think there are problems implicit in the conclusion. At some point late in the book the language begins to slip so that those who are being atoned become not only participants but agents of God's atoning work. 'Missional work is atoning', McKnight will say in one place (134). Or 'the local community offers atonement,' he'll say in another (154). In other words, it is not just God doing the atoning anymore.

This isn't really what McKnight means--at the end of his book he's really just trying to point us in the right direction and isn't going into a lot of detail. It is a concern of trajectory, however, and not a small one. If our gospel-talk removes attention from God as the primary ongoing author and perfecter not only of creation but of our lives of faith, then the mission will curve in on itself. We've seen this time and time again, and that's what the initial quote was addressing. If not in the homogeneous enclaves of market-driven church growth movements, then in the colonialist enterprises of global mission efforts--we say 'thanks for the gospel, God, we'll take it from here.'

McKnight doesn't intend to leave it that way, in fact the final chapter talks about baptism, Eucharist and prayer, but these are not drawn out in the ways that make them so crucial. I hope this leaves readers of McKnight's very good book begging for something more; something to answer that quote with which we began; something to say what kind of a community the atonement has made.

That's a quote from Michael Emerson and Christian Smith's Divided by Faith, which Scot McKnight utilizes to introduce his book: A Community Called Atonement. The context of the quote is the observation that 90% of American churches contain 90% people of the same colour.

McKnight suggests that those 'processes' have much to do with the way churches 'package' the 'gospel' (p. 5). In this book McKnight does not fully address our church-dynamics but aims to bring a full-bodied approach to understanding the gospel so churches can think straight.

One way to talk about how we understand the gospel is to talk about 'atonement', or, the question of how the gospel works' (p. 1). Any attempt to do this must be done with a certain 'postmodern humility,' McKnight believes, because we can only reach into God's side of the story by use of metaphor, and because we can only speak of our side from within our limited contexts. Since no biblical or traditional atonement metaphor appears intent on supplying a comprehensive or exclusive account of the gospel of Christ, instead of looking for a 'winner' McKnight makes the not-so-modest attempt to hold them all together (ch. 11).

The attempt is an interesting one, and McKnight does it well. He begins in part one with Jesus, humanity as the image (or Eikon) of God, with sin and eternity, and with church and Christian practice--the idea being that the gospel is all about these things. In part two he examines the different 'moments' of the atonement--from Christmas to Cross to Easter to Pentecost--arguing that none says all that needs to be said, and giving a compelling picture of the gospel and its intended effects.

In part three McKnight examines the different ways the gospel story was narrated early on--first in the implications of Jesus himself (who framed the events of passion week in terms of Passover and liberation), then in the explanations of the apostle Paul (which serve up a well-told account of today's debate about 'justification'), and then in the reflections of early church theologians Irenaeus and Athanasius (who spoke of it in terms of God's 'recapitulation' of dead humanity).

Rather than put them in competition, after a short synopsis of atonement theories, McKnight coins a phrase which he thinks sums them up: The accomplishment of the gospel is 'identification for incorporation' (107). Whether we're talking about Jesus ransoming from death, satisfying his own judgment of sin, substituting as a punishment for sin, representing us before God, recapitulating us to our proper life, or even providing a moral example of self-giving love, it all adds up to identification for incorporation:

'Jesus became what we are so that we could become what he is.'

As McKnight explains it, Jesus' death on the cross (and perhaps descent into hell) are the extent of God with us; his identification 'all the way down' (110). Furthermore (to use a Barthian turn of phrase), Jesus' resurrection and sending of the Spirit are the extent of us with God; an incorporation into God's own life which goes all the way into eternity and all the way into our lives here on earth.

Normally a book on the atonement might end here, except that McKnight wants to stress the point about incorporation; about our side; about atonement as an act of God which has personal and social implications in the here and now. These implications are not subsidiary byproducts but constitutive elements of the work of the gospel (126). That's not to say that the effect of the gospel depends upon our enactment of it, but that there is a 'potential performative reciprocity in the redemptive work of God' (29).

In other words, the gospel gives birth to a new humanity--on earth as in heaven--complete with new fellowship, just praxis, and mission for a whole world. Thus the book's title: implying that atonement does not end at a divine declaration of our 'savedness' but enfolds us as participants in ours and creation's redemption.

This is all well and good--and I do recommend the book highly--but I was left with a couple practical concerns. The first is that forgiveness is considered synonymous with reconciliation (30). If you think about the difference between forgiving someone and healing a relationship with them, you will recognize how that conflation of terms might collapse the participatory action of this newfound atonement community in all kinds of unhelpful ways.

The second concern can be seen if we go back to that first quote above. If attentiveness to our gospel 'processes' are important, I think there are problems implicit in the conclusion. At some point late in the book the language begins to slip so that those who are being atoned become not only participants but agents of God's atoning work. 'Missional work is atoning', McKnight will say in one place (134). Or 'the local community offers atonement,' he'll say in another (154). In other words, it is not just God doing the atoning anymore.

This isn't really what McKnight means--at the end of his book he's really just trying to point us in the right direction and isn't going into a lot of detail. It is a concern of trajectory, however, and not a small one. If our gospel-talk removes attention from God as the primary ongoing author and perfecter not only of creation but of our lives of faith, then the mission will curve in on itself. We've seen this time and time again, and that's what the initial quote was addressing. If not in the homogeneous enclaves of market-driven church growth movements, then in the colonialist enterprises of global mission efforts--we say 'thanks for the gospel, God, we'll take it from here.'

McKnight doesn't intend to leave it that way, in fact the final chapter talks about baptism, Eucharist and prayer, but these are not drawn out in the ways that make them so crucial. I hope this leaves readers of McKnight's very good book begging for something more; something to answer that quote with which we began; something to say what kind of a community the atonement has made.

Monday, December 15, 2014

Appreciating the Book of Common Prayer: Building from rather than dismissing it

Last week as I shared what I appreciate about the Book of Common Prayer (see parts 1, 2 & 3), there was to be no implication that it should be the modus operandi for all worship and prayer. I would suggest, however, that all corporate worship aspire to its achievements.

It is a sad day indeed where confession is replaced with self-expression, creed with sentimentality, and thoughtfulness with spontaneity. It is a sad day, also, when traditional liturgy becomes meaningless rote and rhythm, all but left for dead as it rolls off our tongues.

That's why I appreciated the effort put into it by our student-leaders at Trinity College last week. I was particularly moved to prayer by the leadership of Denis Adide, who took the closing intercessions of the BCP and added to them creatively so that we came to those same-old lines with renewed theological attentiveness, personal conviction, and global concern.

Previously I mentioned these intercessions (shown below in italics) as a fine lead-up to the Collect for Peace, but now read them with Denis's additions. You'll see what I mean, and you'll see what is possible when you make the most of your liturgical sources rather than dismiss them in favour of pure spontaneity.

After the Lord's Prayer, the leader, standing, prays:

Because at times we, knowing you are King,

do not relinquish the thrones in our hearts;

recoil from the lepers; hide from the sick;

approach your table with contemptuous hearts;

ignore your voice as it leads us from temptation delivering ourselves into evil:

O Lord, shew thy mercy upon us.

(All) And grant us thy salvation.

For reminding us by her presence that we are not sovereign and pointing us to the fact that the earth is yours. That she responds by your Spirit to the office you have called her,

O Lord, save the Queen.

And mercifully hear us when we call upon thee.

Because it is a broken people that you choose to reach into a broken world, pour your Spirit in abundance and teach your church to break, so that what is from heaven may flood the earth. Give wisdom, integrity, faithfulness:

Endue thy ministers with righteousness.

And make thy chosen people joyful.

Because it is in a broken world that you begin your work, where broken people reject you to reject their own brokenness, stand with the persecuted and the oppressed:

O Lord, save thy people.

And bless thine inheritance.

As the two hundred school girls nestle among thorns far away from home, or the refugees flee the Islamic state: fathers bury sons; daughters become orphans; the sword is wielded hastily and our rivers turn to blood. We plead:

Give peace in our time, O Lord.

Because there is none other that fighteth for us, but only thou, O God.

Peace in our time may not quench the desires that return us to that tree of disobedience. Search us and know us, test us and know our thoughts, uproot the wickedness that nestles deep:

O God make clean our hearts within us.

And take not thy Holy Spirit from us.

It is a sad day indeed where confession is replaced with self-expression, creed with sentimentality, and thoughtfulness with spontaneity. It is a sad day, also, when traditional liturgy becomes meaningless rote and rhythm, all but left for dead as it rolls off our tongues.

That's why I appreciated the effort put into it by our student-leaders at Trinity College last week. I was particularly moved to prayer by the leadership of Denis Adide, who took the closing intercessions of the BCP and added to them creatively so that we came to those same-old lines with renewed theological attentiveness, personal conviction, and global concern.

|

| The steps leading from Stoke House down to the Chapel at Trinity College Bristol |

After the Lord's Prayer, the leader, standing, prays:

Because at times we, knowing you are King,

do not relinquish the thrones in our hearts;

recoil from the lepers; hide from the sick;

approach your table with contemptuous hearts;

ignore your voice as it leads us from temptation delivering ourselves into evil:

O Lord, shew thy mercy upon us.

(All) And grant us thy salvation.

For reminding us by her presence that we are not sovereign and pointing us to the fact that the earth is yours. That she responds by your Spirit to the office you have called her,

O Lord, save the Queen.

And mercifully hear us when we call upon thee.

Because it is a broken people that you choose to reach into a broken world, pour your Spirit in abundance and teach your church to break, so that what is from heaven may flood the earth. Give wisdom, integrity, faithfulness:

Endue thy ministers with righteousness.

And make thy chosen people joyful.

Because it is in a broken world that you begin your work, where broken people reject you to reject their own brokenness, stand with the persecuted and the oppressed:

O Lord, save thy people.

And bless thine inheritance.

As the two hundred school girls nestle among thorns far away from home, or the refugees flee the Islamic state: fathers bury sons; daughters become orphans; the sword is wielded hastily and our rivers turn to blood. We plead:

Give peace in our time, O Lord.

Because there is none other that fighteth for us, but only thou, O God.

Peace in our time may not quench the desires that return us to that tree of disobedience. Search us and know us, test us and know our thoughts, uproot the wickedness that nestles deep:

O God make clean our hearts within us.

And take not thy Holy Spirit from us.

(Thank you to Denis for permission to publish this prayer)

Saturday, December 13, 2014

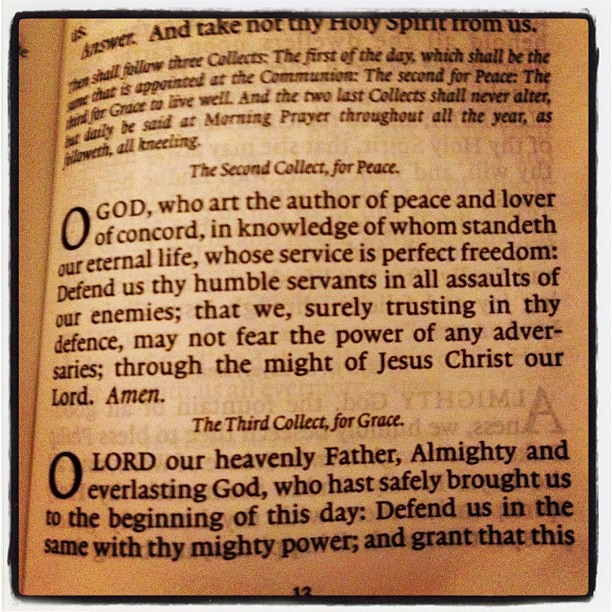

Appreciating the Book of Common Prayer: Collect for Peace

This week as we've been utilizing the Book of Common Prayer for our morning prayers at Trinity College, I've been expressing appreciation for some of its particular qualities.

Thoughtfully prepared corporate prayer has become more and more important to me in recent years. That's not to say I always want to go to prayer. Far from it. Some days it feels like a downright chore. But even then, what gets me there is that I want to want to pray, and on arrival there are certain things I especially want to want to pray.

Aside from the Lord's Prayer, Gloria Patri and Te Deus Laudamus, the part of the BCP I anticipate most (which does appear in other liturgies as well), is the Collect for Peace.

For those unfamiliar with a 'Collect', it is a prayer from the leader at the end of the service which gathers up or 'collects' the intercessions and prayers and confessions that have gone before. There are several, but the Collect for Peace goes like this:

O God, who art the author of peace and lover of concord,

in knowledge of whom standeth our eternal life,

whose service is perfect freedom;

defend us thy humble servants in all assaults of our enemies;

that we, surely trusting in thy defence,

may not fear the power of any adversaries;

through the might of Jesus Christ our Lord.

Amen.

The lines I particularly appreciate are those which--in the midst of a turbulent, fragmented world--lead me to confess God as the 'author of peace and lover of concord,' and to confess my own 'perfect freedom' as a life lived in service to that God.

On the face of it, the Collect for Peace could seem to heighten adversarial attitudes, but I don't read it that way. Rather than pretending one has no adversaries, the prayer leads us to be honest with ourselves. In the same breath as it renounces fear, the prayer entrusts defense into divine hands rather than taking it upon ourselves.

Furthermore, right before the Collects there are a series of short responsive prayers which focus our prayers for society, the church and their leaders, as well as for ourselves. Read responsively, they say:

Shew thy mercy upon us. And grant us thy salvation.

O Lord Save the Queen. And mercifully hear us when we call upon thee.

Endue thy ministers with righteousness. And make thy chosen people joyful.

O Lord, save thy people. And bless thine inheritance.

Give peace in our time, O Lord. Because there is none other that fighteth for us, but only thou, O God.

Make clean our hearts within us. And take not thy Holy Spirit from us.

In my next (and last) post in this series, I'll share how one of our students at Trinity College helped us make sense of these potentially arcane-sounding lines. But for now let me highlight how this rapid succession of beautiful prayers leads poignantly into the Collect for Peace:

As we pray for our leaders we pray for ourselves, and in this we pray for mercy, we pray for 'peace in our time', and we confess that there is 'none other that fighteth' than God.

Thoughtfully prepared corporate prayer has become more and more important to me in recent years. That's not to say I always want to go to prayer. Far from it. Some days it feels like a downright chore. But even then, what gets me there is that I want to want to pray, and on arrival there are certain things I especially want to want to pray.

Aside from the Lord's Prayer, Gloria Patri and Te Deus Laudamus, the part of the BCP I anticipate most (which does appear in other liturgies as well), is the Collect for Peace.

For those unfamiliar with a 'Collect', it is a prayer from the leader at the end of the service which gathers up or 'collects' the intercessions and prayers and confessions that have gone before. There are several, but the Collect for Peace goes like this:

|

| The Collect for Peace, from the Book of Common Prayer |

The lines I particularly appreciate are those which--in the midst of a turbulent, fragmented world--lead me to confess God as the 'author of peace and lover of concord,' and to confess my own 'perfect freedom' as a life lived in service to that God.

On the face of it, the Collect for Peace could seem to heighten adversarial attitudes, but I don't read it that way. Rather than pretending one has no adversaries, the prayer leads us to be honest with ourselves. In the same breath as it renounces fear, the prayer entrusts defense into divine hands rather than taking it upon ourselves.

Furthermore, right before the Collects there are a series of short responsive prayers which focus our prayers for society, the church and their leaders, as well as for ourselves. Read responsively, they say:

Shew thy mercy upon us. And grant us thy salvation.

O Lord Save the Queen. And mercifully hear us when we call upon thee.

Endue thy ministers with righteousness. And make thy chosen people joyful.

O Lord, save thy people. And bless thine inheritance.

Give peace in our time, O Lord. Because there is none other that fighteth for us, but only thou, O God.

Make clean our hearts within us. And take not thy Holy Spirit from us.

In my next (and last) post in this series, I'll share how one of our students at Trinity College helped us make sense of these potentially arcane-sounding lines. But for now let me highlight how this rapid succession of beautiful prayers leads poignantly into the Collect for Peace:

As we pray for our leaders we pray for ourselves, and in this we pray for mercy, we pray for 'peace in our time', and we confess that there is 'none other that fighteth' than God.

Thursday, December 11, 2014

Appreciating the Book of Common Prayer: Te Deum Laudamus

|

| This is the chapel at Trinity College Bristol |

For instance, consider this excerpt from what we prayed today: The Te Deum Laudamus [O God, we praise you]. I won't add much commentary since it speaks for itself, but please just notice the flow.

It builds to a crescendo and hits most or all of the essential notes of worship along the way. It gathers up the pray-er with all creation, calls to mind the great cloud of witnesses, confesses the being and works of the Triune God, and then at its climax prays for mercy and safety from sin.

In the midst of it all there are lines you could chew on the rest of the day--such as 'thou didst not abhor the Virgin's womb'--and lines that are so simple--such as 'we acknowledge thee to be the Lord'--that you'd almost forget to say them (to your peril) if not for morning prayers.

All the earth doth worship thee : the Father everlasting.

To thee all Angels cry aloud : the Heavens, and all the Powers therein.

To thee Cherubin and Seraphin : continually do cry,

Holy, Holy, Holy : Lord God of Sabaoth;

Heaven and earth are full of the Majesty : of thy glory.

The glorious company of the Apostles : praise thee.

The goodly fellowship of the Prophets : praise thee.

The noble army of Martyrs : praise thee.

The holy Church throughout all the world : doth acknowledge thee;

The Father : of an infinite Majesty;

Thine honourable, true : and only Son;

Also the Holy Ghost : the Comforter.

Thou art the King of Glory : O Christ.

Thou art the everlasting Son : of the Father.

When thou tookest upon thee to deliver man : thou didst not abhor the Virgin's womb.

When thou hadst overcome the sharpness of death : thou didst open the Kingdom of Heaven to all believers.

Thou sittest at the right hand of God : in the glory of the Father.

We believe that thou shalt come : to be our Judge.

We therefore pray thee, help thy servants : whom thou hast redeemed with thy precious blood.

Make them to be numbered with thy Saints : in glory everlasting.

O Lord, save thy people : and bless thine heritage.

Govern them : and lift them up for ever.

Day by day : we magnify thee;

And we worship thy Name : ever world without end.

Vouchsafe, O Lord : to keep us this day without sin.

O Lord, have mercy upon us : have mercy upon us.

O Lord, let thy mercy lighten upon us : as our trust is in thee.

O Lord, in thee have I trusted : let me never be confounded.

Tuesday, December 09, 2014

Appreciating the Book of Common Prayer

To my joy, in Morning Prayer at Trinity College this week we're using the Church of England's 17th Century Book of Common Prayer. It's not that I don't appreciate the updated mainstay, the 21st century book of Common Worship--I like that too--but I love the BCP.

To my joy, in Morning Prayer at Trinity College this week we're using the Church of England's 17th Century Book of Common Prayer. It's not that I don't appreciate the updated mainstay, the 21st century book of Common Worship--I like that too--but I love the BCP.This is what we used for morning prayers at King's College while I was studying in Aberdeen--when I was learning to make communal liturgy a central part of my daily life--so there is a degree to which the BCP simply holds significance of continuity for me. But it's more than that. The words and prayers are particularly rich.

Not just because they are in old English. To be honest that really doesn't do that much for me. I remember the KJV from my earliest years, but I was largely brought up on (and sometimes had to fight for) the NIV, so there's little nostalgia-factor in the thees and thous.

Don't get me wrong, there is something sometimes important about conforming one's prayers to the language of people long gone--but saying things like Sabaoth and Cherubin and which art in heaven are not the only reason I like the Book of Common Prayer.

No, for me it's just that there's a series of wonderful lines that are so significant I find myself actually looking forward to them. This week I'd like to highlight a few of the words I find myself hanging on, beginning with the simplest of them all:

world without end

This comes as part of the recurring Gloria Patri, which says in full:

Glory be to the Father,

and to the Son,

and to the Holy Ghost;

as it was in the beginning,

is now, and ever shall be,

world without end. Amen.

This is always a highlight of morning prayer. We say it all together, some with the sign of the cross, and it makes an important declaration for the day.

The refrain is familiar enough in other contexts as well, including Common Worship where it says 'Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit; as it was in the beginning is now and shall be for ever. Amen.'

Clearly the BCP version is not much different--except for these three unique aspects:

- The first time it is said is typically call and response, with the leader calling us to worship with the first part, and the congregation joining in for the remainder;

- it says 'Glory be' rather than simply 'Glory', which makes it feel like a confession befitting any emotional state one might be in on any given day; and

- it ends with those three evocative words which are everlasting in scope but no less creaturely and profound. They call me to look forward with hope, not to escape into an ethereal 'plan B', but into Emmanuel's fulfilment of the Creator's plan A.

Saturday, December 06, 2014

A Problem with the Problem-oriented Gospel

'[S]oteriology will be cautious about ordering its material around some theme (such as 'facing' or 'hospitality'), or as a response to a perceived problem (such as 'violence'). Thematic or problem-oriented presentations are commonly nominalist and moralistic, since their centre of gravity lies not in the irreducible person and work of God but rather in some human experience or action of which all theological talk of salvation is symbolic. Soteriology must fall under the rule which governs all dogmatic work, namely 'the claim of the First Commandment'. To speak of dogmatic soteriology as biblical reasoning is to press home the noetic application of that claim.'

- John Webster,

'"It was the Will of the Lord to Bruise Him":

Soteriology and the Doctrine of God'

Monday, December 01, 2014

Vonnegut, on writing

|

| Kurt Vonnegut, waving like his gnome. |

'The most radical, audacious thing to think is that there might be some point to working hard and thinking hard and reading hard and writing hard and trying to be of service.'

'Reading and writing are in themselves subversive acts. What they subvert is the notion that things have to be the way they are, that you are alone, that no one has ever felt the way you have. What occurs to people when they read Kurt is that things are much more up for grabs than they thought they were. The world is a slightly different place just because they read a damn book. Imagine that.'

- Mark Vonnegut, speaking about his father Kurt

Sunday, November 30, 2014

Kurt Vonnegut's 'The Unicorn Trap'

Ivy sat down at the table, and put her feet up on it. 'If a body gets stuck in the ruling classes through no fault of their own,' she said, 'they got to rule or have folks just lose all respect for government.' She scratched herself daintily. 'Folks got to be governed.'

'To their sorrow,' said Elmer.

'Folks got to be protected,' said Ivy, 'and armor and castles don't come cheap.'

Elmer rubbed his eyes. 'Ivy, would you tell me what it is we're being protected from that's so much worse than what we've got?' he said. 'I'd love to have a look at it, and then make up my own mind about what scares me most.'

Ivy wasn't listening to him. She was thrilled to the approach of hoofbeats.

'To their sorrow,' said Elmer.

'Folks got to be protected,' said Ivy, 'and armor and castles don't come cheap.'

Elmer rubbed his eyes. 'Ivy, would you tell me what it is we're being protected from that's so much worse than what we've got?' he said. 'I'd love to have a look at it, and then make up my own mind about what scares me most.'

Ivy wasn't listening to him. She was thrilled to the approach of hoofbeats.

- Kurt Vonnegut, 'The Unicorn Trap'

Saturday, November 29, 2014

The Blog as a Commonplace Book

Now nine years old, This Side of Sunday hereby enters a new season of its existence, as a commonplace book. I'm not sure that's much different than what it's been to date, except it signals that I will be (and have more recently been) doing the bulk of my own thinking and writing elsewhere.

Positively, it means I'm not walking away from the blog, but am embracing what it's become. As Alan Jacobs explains it, the historic goal of the commonplace book

It may not be handwritten, but it will be similar here. No cut and paste: just mulling the words over some more as I re-scribe them, with the added bonus that they'll be shared and maybe even talked about with others.

I have always liked jotting down poignant quotes--usually for myself; often tucked away in a notebook and forgotten. Now I do most of it here. So many of my good friends and conversation partners I only see online. As my tag-line used to say: this is where I gather thoughts for hopeful conversations.

Anyway: thought I'd let you know. Some of you have been with me for years--and our interactions have been as formative for me as they were enjoyable. Much appreciated.

HT Wesley Hill

Positively, it means I'm not walking away from the blog, but am embracing what it's become. As Alan Jacobs explains it, the historic goal of the commonplace book

'was to gather a collection of the wisest statements, usually of the ancients, for future meditation. And here the key thing was to write the words in your own hand ... by laboriously and carefully copying out the insights of people smarter than you, you could absorb and internalize their wisdom.'

It may not be handwritten, but it will be similar here. No cut and paste: just mulling the words over some more as I re-scribe them, with the added bonus that they'll be shared and maybe even talked about with others.

I have always liked jotting down poignant quotes--usually for myself; often tucked away in a notebook and forgotten. Now I do most of it here. So many of my good friends and conversation partners I only see online. As my tag-line used to say: this is where I gather thoughts for hopeful conversations.

Anyway: thought I'd let you know. Some of you have been with me for years--and our interactions have been as formative for me as they were enjoyable. Much appreciated.

HT Wesley Hill

Friday, November 28, 2014

Advice from Gilead, on prophets and pharisees

'But people of any degree of religious sensibility are always vulnerable to the accusation that their consciousness or their understanding does not attain to the highest standards of their faith, because that is always true of everyone.... It seems that the spirit of self-righteousness this article deplores is precisely the spirit in which it is written. Of course he's right about many things, one of them being the destructive potency of religious self-righteousness.'

- John Ames

in Marilynne Robinson's Gilead

pages 162 and 166

in Marilynne Robinson's Gilead

pages 162 and 166

Sunday, November 23, 2014

Advice from Gilead, 'against defensiveness in principle'

'Boughton takes a very dim view of him [Ludwig Feuerbach], because he unsettled the faith of many people, but I take issue as much with those people as with Feuerbach. It seems to me some people just go around looking to get their faith unsettled.'

- John Ames

in Marilynne Robinson's Gilead

pages 176 and 27

in Marilynne Robinson's Gilead

pages 176 and 27

Thursday, November 20, 2014

Advice from Gilead: 'Don't look for proofs'

I'm not saying never doubt or question. The Lord gave you a mind so that you would make honest use of it. I'm saying you must be sure that the doubts and questions are your own, not, so to speak, the mustache and walking stick that happen to be the fashion of any particular moment.'

- John Ames

in Marilynne Robinson's Gilead

page 204

in Marilynne Robinson's Gilead

page 204

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

'So to be forgiven is only half the gift.'

'And grace is the great gift. So to be forgiven is only half the gift. The other half is that we also can forgive, restore, and liberate, and therefore we can feel the will of God enacted through us, which is the great restoration of ourselves to ourselves.'

'He could knock me down the stairs and I would have worked out the theology for forgiving him before I reached the bottom. But if he harmed you in the slightest way, I'm afraid theology would fail me. That may be one great part of what I fear, now that I think of it.'

- John Ames

in Marilynne Robinson's Gilead

pages 169-170, 183-184, 216

in Marilynne Robinson's Gilead

pages 169-170, 183-184, 216

Monday, November 17, 2014

'The heroism of routine'

'In one way we have been reacquainted with a local and unexciting heroism that we have ignored in our relentless pursuit of drama.... the heroism of routine.'

We tend not to notice them until something goes dramatically right or wrong, but every day there are thousands of public servants and socially involved individuals who carry it out in millions of small but significant acts.

- Rowan Williams, Writing in the Dust:

Reflections on 11th September and its Aftermath, 47-48

Reflections on 11th September and its Aftermath, 47-48

We tend not to notice them until something goes dramatically right or wrong, but every day there are thousands of public servants and socially involved individuals who carry it out in millions of small but significant acts.

Sunday, November 16, 2014

The Worst Form of Forgiveness

'It could be true that my interest in abstractions, which would have been forgiven first on grounds of youth and then on grounds of eccentricity, is now being forgiven on grounds of senility, which would mean people have stopped trying to see the sense in the things I say the way they once did. That would be by far the worst form of forgiveness.'

'It could be true that my interest in abstractions, which would have been forgiven first on grounds of youth and then on grounds of eccentricity, is now being forgiven on grounds of senility, which would mean people have stopped trying to see the sense in the things I say the way they once did. That would be by far the worst form of forgiveness.'

- John Ames

In other words, merely being tolerated is experienced as a far worse form of forgiveness than that which is at least a kind of forbearance.

Marilynne Robinson's Gilead is a series of profound asides.

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

'In the global village, fire can jump more easily from roof to roof.'

Not long ago a soldier was shot and killed while guarding the National War Memorial in Ottawa, the capital of Canada. The shooter then hijacked a car to the nearby Parliament building, ran in, and got all the way up to the door of the House of Commons before he was stopped and ultimately killed as well. It was rattling.

Earlier I wrote some questions about our responses to that incident. As I watched the reactions on old and new media, something felt 'off' to me. Something about the upsurge in images of the flag seemed like echoing evocations of a kind of burgeoning Canadian exceptionalism. It's not that we shouldn't rally around the call to give of ourselves for a safer, more tolerant country. It's just that it felt more parochial than peaceable; so nationalistic that it sounded naive.

I'm still trying to put my thumb on what I mean by that, but I picked up a little book by Rowan Williams the other day which might help to capture it. The book is called Writing in the Dust: Reflections on 11th September and its Aftermath.

I'm still trying to put my thumb on what I mean by that, but I picked up a little book by Rowan Williams the other day which might help to capture it. The book is called Writing in the Dust: Reflections on 11th September and its Aftermath.

Now, I'm still not sure whether the incident in Ottawa is best classified as straight-up terrorism or not, but let's say it is: The question still stands whether we allow the terms of terrorism to frame the meaning we make of these events.

I'll leave this here as something more to think about. What does it mean to be part of a country today? What citizenship frames our approach to the clashes and conflicts of our day? Williams writes in Britain in 2002, but the thoughts and prayers still hold:

Earlier I wrote some questions about our responses to that incident. As I watched the reactions on old and new media, something felt 'off' to me. Something about the upsurge in images of the flag seemed like echoing evocations of a kind of burgeoning Canadian exceptionalism. It's not that we shouldn't rally around the call to give of ourselves for a safer, more tolerant country. It's just that it felt more parochial than peaceable; so nationalistic that it sounded naive.

I'm still trying to put my thumb on what I mean by that, but I picked up a little book by Rowan Williams the other day which might help to capture it. The book is called Writing in the Dust: Reflections on 11th September and its Aftermath.

I'm still trying to put my thumb on what I mean by that, but I picked up a little book by Rowan Williams the other day which might help to capture it. The book is called Writing in the Dust: Reflections on 11th September and its Aftermath.Now, I'm still not sure whether the incident in Ottawa is best classified as straight-up terrorism or not, but let's say it is: The question still stands whether we allow the terms of terrorism to frame the meaning we make of these events.

I'll leave this here as something more to think about. What does it mean to be part of a country today? What citizenship frames our approach to the clashes and conflicts of our day? Williams writes in Britain in 2002, but the thoughts and prayers still hold:

'It feels as though some kind of contract has been broken, some unspoken agreement guaranteeing that we in the North Atlantic world would be spared the majority human experience of insecurity and physical dread.

What Faustian contract did we think had been made on our behalf? How would we imagine that, in a shrinking world, we could for ever postpone being touched by that majority experience? In the global village, fire can jump more easily from roof to roof.

Globalisation is not just an economic matter, the removal of pointless and archaic barriers to the movement of capital; not just a cultural matter, a McDonald's in every village in Papua New Guinea. It isn't even a matter of the free flow of information, so that images of the triumphant culture are everywhere (though that is so strong an element in the resentment of the non-Western world).

All these things have one sobering consequence: suffering in one region is connected with action in another...

Global economics is impressive in theory as regards its potential for regenerating local practice; but in reality it is seen as managed for the sake of those who are already victorious... Globalisation means that we are involved in dramas we never thought of, cast in roles we never chose. As we protest at how much the West is hated, how we never meant to oppress or diminish other cultures ... we must try not to avoid the pain of grasping that we are not believed.

The horror of being vulnerable to terrorist violence might open our eyes to the vulnerability that in fact underlies the whole globalisation process... [T]he sudden and literally brutal discovery that there is not contract to protect people like us from death and danger, and the humiliation of not knowing even where the threat really comes from or when or how it may strike again -- the sheer surprise may yet have its force in persuading us to make some connections...

The trauma can offer a breathing space; and in that space there is the possibility of recognising that we have had an experience that is not just a nightmarish insult to us but a door into the suffering of countless other innocents, a suffering that is more or less routine for them in their less regularly protected environments.

And in the face of extreme dread, we may become conscious, as people often do, of two very fundamental choices. We can cling harder and harder to the rock of our threatened identity -- a choice, finally, for self-delusion over truth; or we can accept that we shall have no ultimate choice but to let go, and in that letting go, give room to what's there around us -- to the sheer impression of the moment, to the need of the person next to you, to the fear that needs to be looked at, acknowledged and calmed (not denied).

If that happens, the heart has room for many strangers, near and far. There is a global hospitality possible too in the presence of death.'

Monday, November 03, 2014

Re-reading 'The Imitation of Christ'

For a while I've been thinking about the merits of imitatio Christi and participatio Christi as paradigms for speaking of the Christian life. More and more I'm compelled to think the latter must make sense of the former, else we're presuming to reproduce that which we can only be transformed by.

So it is with interest that I picked up Thomas à Kempis' The Imitation of Christ last week in order to see if it's a theological friend or foe. (I wouldn't come to as brunt a conclusion as that, but you know what I mean). It has been over a decade since I read it, and as I've thought about the above it has been on my mind to go back and see what kind of nuance it gives to the life that it describes.

Thus far it has been an arresting experience for a number of reasons, not least of which being that it's one more encounter with that great cloud of witnesses where one's outlook gets checked by the democracy of the dead. For me, reading a 15th century Christian mystic is about as different as it gets, and so it brings about a confrontation wherein I can learn as much about myself as I can about the Other.

What has jumped out off the page at me early on is the context surrounding The Imitation of Christ's most famous quote. It's in book 1 chapter 3, and it has more to it than I remembered or noticed before. You've probably heard verse 4 before, which says:

There's plenty going on in this sentence---enough that I've had occasion both to ruminate over and balk at it over the years. On one hand, yes, humble self-knowledge is hugely important. Experience has only borne this out for me. On the other hand, however, the statement itself seems to lean disturbingly into anti-intellectualism and over-confidence. In my experience it is platitudes like this that provide support for all kinds of projections being thrust upon the divine (and then upon others) on the basis of private intuition.

However, what I'm remembering as I read this text is that, like the biblical Proverbs, The Imitation of Christ reads better when the one-liners work in tension with one another, rather than as proof-texts for whatever we want to say.

In fact, as it turns out, there's plenty in the preceding verses (2 and 3) to give that (in)famous quote its proper depth and texture. Such as:

That's right before we come to our famous line. By then it should be clear that there's simply no room for arrogant self-projection or anti-intellectual self-righteousness.

It is evident from the rest of book one that Thomas à Kempis was as worried about the prideful power of the learned in his time as I might be about the vain projection of the privately pious in mine.

But at the intersection of our times we are forced to look past our reactions to the heart of the text and to see if there's something more constructive going on. And as I read this book it seems to me that if I were to express my concern to him Thomas à Kempis might happily adopt my counterpoint as a complement to what he's said. Namely:

In other words, this is not about the exaltation either of private piety or of advanced reason as a way to God; it is about having these freed from the vanity of ingrown pursuits for the humble receptivity of reflective participation in the life of Christ with others.

So it is with interest that I picked up Thomas à Kempis' The Imitation of Christ last week in order to see if it's a theological friend or foe. (I wouldn't come to as brunt a conclusion as that, but you know what I mean). It has been over a decade since I read it, and as I've thought about the above it has been on my mind to go back and see what kind of nuance it gives to the life that it describes.

Thus far it has been an arresting experience for a number of reasons, not least of which being that it's one more encounter with that great cloud of witnesses where one's outlook gets checked by the democracy of the dead. For me, reading a 15th century Christian mystic is about as different as it gets, and so it brings about a confrontation wherein I can learn as much about myself as I can about the Other.

What has jumped out off the page at me early on is the context surrounding The Imitation of Christ's most famous quote. It's in book 1 chapter 3, and it has more to it than I remembered or noticed before. You've probably heard verse 4 before, which says:

'The humble knowledge of one's self is a surer way to God than a deep search after knowledge.'

There's plenty going on in this sentence---enough that I've had occasion both to ruminate over and balk at it over the years. On one hand, yes, humble self-knowledge is hugely important. Experience has only borne this out for me. On the other hand, however, the statement itself seems to lean disturbingly into anti-intellectualism and over-confidence. In my experience it is platitudes like this that provide support for all kinds of projections being thrust upon the divine (and then upon others) on the basis of private intuition.

However, what I'm remembering as I read this text is that, like the biblical Proverbs, The Imitation of Christ reads better when the one-liners work in tension with one another, rather than as proof-texts for whatever we want to say.

In fact, as it turns out, there's plenty in the preceding verses (2 and 3) to give that (in)famous quote its proper depth and texture. Such as:

'He to whom the eternal Word speaketh, is set free from a multitude of opinions.'

'A pure, simple, and steadfast spirit is not distracted by the number of things to be done; because it performs them all to the honour of God, and endeavours to be at rest within itself from all self-seeking.'

'And these do not draw him to the desires of an inordinate inclination; but he himself bends them to the rule of right reason.'

'Who has a stronger conflict than he who strives to overcome himself?'

'All perfection in this life is attended with a certain imperfection, and all our speculation with a certain obscurity.'

That's right before we come to our famous line. By then it should be clear that there's simply no room for arrogant self-projection or anti-intellectual self-righteousness.

It is evident from the rest of book one that Thomas à Kempis was as worried about the prideful power of the learned in his time as I might be about the vain projection of the privately pious in mine.

But at the intersection of our times we are forced to look past our reactions to the heart of the text and to see if there's something more constructive going on. And as I read this book it seems to me that if I were to express my concern to him Thomas à Kempis might happily adopt my counterpoint as a complement to what he's said. Namely:

A humble search after knowledge is a surer way to God than a deep knowledge of one's self.

In other words, this is not about the exaltation either of private piety or of advanced reason as a way to God; it is about having these freed from the vanity of ingrown pursuits for the humble receptivity of reflective participation in the life of Christ with others.

Thursday, October 30, 2014

Preparing for Church Leadership: An Example of Theological Reflection in Practice

Still in my first month as Tutor in Theology at Trinity College, Bristol, I'm already enjoying my first Reading Week. It is affording me the opportunity to familiarize myself with our college handbooks, and to prepare for my first teaching and preaching assignments.

In the process I have become very impressed with this college's intentionality of integration between practical and theological learning. It is that dual focus on ministry and academy which so attracted me to this school, and I am happy to report it in fact exceeds my expectations. I am excited to contribute to what this theological college is about.

As a case in point--and as a blog post in its own right--just let me show you one page of our Practical Training Handbook, put together by our Tutor in Practical Theology, Rev'd Sue Gent. It is one of six reports that come in 'Appendix 3: Forms for us in Contextual Training and Church Placements'--and the simple but poignant line of questioning goes like this:

------

Meeting Report

(complete this form if you were an observer only)

Name/Date/Occasion:

Was the meeting well arranged?

What were its aims?

Were they achieved?

Who was in control, formally?

Who held the real power?

What interesting dynamics did you observe?

How would you describe the spiritual atmosphere of the meeting?

Your conclusion of the proceedings:

------

This could of course simply be written off as just one more of the many forms that a student has to fill out in the course of his or her training. However, if you look at it closely (especially at the questions in the middle) I think it proves a helpful, perceptive piece of preparatory pastoral reflection.

The questions themselves are not heavily inflected with theology, but embedded as they are within a considerable amount of theological learning and reflection they provide an opportunity to think about the power-dynamics of leadership in a culturally sensitive and contextually specific way.

Incidentally, if you're interested in checking out Trinity College, we have an Open Day coming up that is precisely designed for that purpose.

In the process I have become very impressed with this college's intentionality of integration between practical and theological learning. It is that dual focus on ministry and academy which so attracted me to this school, and I am happy to report it in fact exceeds my expectations. I am excited to contribute to what this theological college is about.

As a case in point--and as a blog post in its own right--just let me show you one page of our Practical Training Handbook, put together by our Tutor in Practical Theology, Rev'd Sue Gent. It is one of six reports that come in 'Appendix 3: Forms for us in Contextual Training and Church Placements'--and the simple but poignant line of questioning goes like this:

------

Meeting Report

(complete this form if you were an observer only)

Name/Date/Occasion:

Was the meeting well arranged?

What were its aims?

Were they achieved?

Who was in control, formally?

Who held the real power?

What interesting dynamics did you observe?

How would you describe the spiritual atmosphere of the meeting?

Your conclusion of the proceedings:

------

This could of course simply be written off as just one more of the many forms that a student has to fill out in the course of his or her training. However, if you look at it closely (especially at the questions in the middle) I think it proves a helpful, perceptive piece of preparatory pastoral reflection.

The questions themselves are not heavily inflected with theology, but embedded as they are within a considerable amount of theological learning and reflection they provide an opportunity to think about the power-dynamics of leadership in a culturally sensitive and contextually specific way.

Incidentally, if you're interested in checking out Trinity College, we have an Open Day coming up that is precisely designed for that purpose.

Monday, October 27, 2014

The Shooting in Ottawa: Discerning Motives, Meanings, and Responses

A Canadian soldier is shot dead at the National War Memorial before the assailant runs to Parliament and is shot by the Sergeant-at-Arms and dies on the doorstep of the House of Commons.

Based on those circumstances, one might be forgiven for interpreting the incident in terms of national security, situating it within a battle of political ideologies and the war on terror. But it matters that we reflect carefully on such things. Our interpretation of the event goes a long way in determining our short- and long-term responses; our cultural and societal attitudes.

Based on those circumstances, one might be forgiven for interpreting the incident in terms of national security, situating it within a battle of political ideologies and the war on terror. But it matters that we reflect carefully on such things. Our interpretation of the event goes a long way in determining our short- and long-term responses; our cultural and societal attitudes.

Thus it is with interest that I read two articles today, probing deeper into motives and meaning:

A heart-wrenching letter from the mother of the Ottawa shooter, which doubts he "acted on behalf of some grand ideology or for a political motive."

A statement from the RCMP that they are examining "persuasive evidence that [the] attack was driven by ideological and political motives."

The question I raised elsewhere and am simply recording here is this: What exactly is at stake in proving one thing or the other?

Prompted further, I'm lead to think of 'terrorism' as this name we give to things that fall outside the usual terms of war--such as premeditated but surprise attacks on civilian turf. Whether we like to take the long-term view and admit it or not, these are usually (rightly or wrongly or maybe a bit of both) in response to some grievance against the people who call that turf home.

The main weapon in terrorist acts is the fear they initiate, and the main motive is probably to strike back at that perceived enemy with an impact that exceeds one's actually ability to counter them force-for-force.

What complicates matters is that when we've gone off on a 'war on terror' (rightly or not), we possibly exacerbate the conditions that might invite that kind of terror even more. Depending on the terms of engagement and the location of the terrorists, we may even duplicate that terror on foreign soil (inadvertently or justifiably or not).

What complicates matters in this case, I suppose, is that even if this man was caught up in ideological or cultural-political motives, his (possible) mental illness and criminal history may well be as big a catalyst for what he's ended up doing as any kind of battle he perceived himself to be fighting.

I guess my concern is the speed with which the incident was coloured in nationalist, terrorist overtones, even before a proper investigation could be had.

Why? Because by labelling it simply and only a terrorist act we may set our sights and spend our funds on nationalist security issues (not to mention prompt anti-religious rhetoric) when more (or as much) attention might be warranted by the social conditions and infrastructures at play within our nation itself.

In other words, the enemy is demonized and the us/them narratives are exacerbated while underlying issues may not only go unaddressed but perhaps even get perpetuated.

That's not to suggest this killing is to blame on the judicial or penal systems which served as this troubled man's primary places of engagement with the government he would later attack. It is simply to say that if we want to get to the bottom of the underlying problems we may do well do avoid the entrenchment of battle lines that set us up in postures of attack and defence in return.

Based on those circumstances, one might be forgiven for interpreting the incident in terms of national security, situating it within a battle of political ideologies and the war on terror. But it matters that we reflect carefully on such things. Our interpretation of the event goes a long way in determining our short- and long-term responses; our cultural and societal attitudes.

Based on those circumstances, one might be forgiven for interpreting the incident in terms of national security, situating it within a battle of political ideologies and the war on terror. But it matters that we reflect carefully on such things. Our interpretation of the event goes a long way in determining our short- and long-term responses; our cultural and societal attitudes.Thus it is with interest that I read two articles today, probing deeper into motives and meaning:

A heart-wrenching letter from the mother of the Ottawa shooter, which doubts he "acted on behalf of some grand ideology or for a political motive."

A statement from the RCMP that they are examining "persuasive evidence that [the] attack was driven by ideological and political motives."

The question I raised elsewhere and am simply recording here is this: What exactly is at stake in proving one thing or the other?

Prompted further, I'm lead to think of 'terrorism' as this name we give to things that fall outside the usual terms of war--such as premeditated but surprise attacks on civilian turf. Whether we like to take the long-term view and admit it or not, these are usually (rightly or wrongly or maybe a bit of both) in response to some grievance against the people who call that turf home.

The main weapon in terrorist acts is the fear they initiate, and the main motive is probably to strike back at that perceived enemy with an impact that exceeds one's actually ability to counter them force-for-force.

What complicates matters is that when we've gone off on a 'war on terror' (rightly or not), we possibly exacerbate the conditions that might invite that kind of terror even more. Depending on the terms of engagement and the location of the terrorists, we may even duplicate that terror on foreign soil (inadvertently or justifiably or not).

What complicates matters in this case, I suppose, is that even if this man was caught up in ideological or cultural-political motives, his (possible) mental illness and criminal history may well be as big a catalyst for what he's ended up doing as any kind of battle he perceived himself to be fighting.

I guess my concern is the speed with which the incident was coloured in nationalist, terrorist overtones, even before a proper investigation could be had.

Why? Because by labelling it simply and only a terrorist act we may set our sights and spend our funds on nationalist security issues (not to mention prompt anti-religious rhetoric) when more (or as much) attention might be warranted by the social conditions and infrastructures at play within our nation itself.

In other words, the enemy is demonized and the us/them narratives are exacerbated while underlying issues may not only go unaddressed but perhaps even get perpetuated.

That's not to suggest this killing is to blame on the judicial or penal systems which served as this troubled man's primary places of engagement with the government he would later attack. It is simply to say that if we want to get to the bottom of the underlying problems we may do well do avoid the entrenchment of battle lines that set us up in postures of attack and defence in return.

Saturday, October 18, 2014

39

Typically around my birthday I add another entry to my running list of life-influencing books, albums and films. I was busy moving across the ocean when I turned thirty-nine this year, but here we are without further adieu:

Once I'd voiced my interest in country music only in the lyrically-rich and musically-creative vein of Ryan Adams and the Cardinals, my friends James and Tyler sent a few recommendations my way--including Dawes and, of course, Jason Isbell. This past year I listened to music mostly in my office and, whether I was emailing or writing sermons, Southeastern seemed to be on constant repeat. At times I would put it away for awhile and only come back to it with more conviction.

Once I'd voiced my interest in country music only in the lyrically-rich and musically-creative vein of Ryan Adams and the Cardinals, my friends James and Tyler sent a few recommendations my way--including Dawes and, of course, Jason Isbell. This past year I listened to music mostly in my office and, whether I was emailing or writing sermons, Southeastern seemed to be on constant repeat. At times I would put it away for awhile and only come back to it with more conviction.

In the end it is Isbell's ability to be easy-going and earnest at once which I think draws me in, and of course the music is just excellent. 'Cover Me Up' and 'Live Oak' are tremendous songs, notable almost as much for their reserve as their richness (click a link and give it a listen while you read on). As the geographically-informed album title indicates, the storied-songs come from a place. It's a world I've never inhabited; nonetheless the songs hit home.

Brad Pitt recommended this book to me (ha ha), and I'm glad I wasn't thrown off by the usual (well-warranted) worries that seeing the movie first would prove to have ruined the book. The film is very much about Oakland A's manager Billy Beane, but the book is also about the stat-keeping baseball hobbyists who stood behind Beane's revolutionary approach, and the marginalized players it came to benefit (and even save). What's so compelling about this story is how lovers of the game were able to set its profiteers on edge, and for a time almost take baseball back.

Most of my list of non-fiction books have to do with my area of study (theology), but this one belongs right there with them because of the complexity with which its human subjects are portrayed. These include not only Billy Beane but also Bill James, the stat-nerd behind sabermetrics, and Chad Bradford, the pitcher with the freaky-weird wind-up. What stuck with me the most, however, was the chapter on Scott Hatteberg, who said 'poor hitters make the best hitting coaches. They don't try to make you like them, because they sucked.'

Another memorable line comes from James, who says 'you have to do something right to get an error; even if the ball is hit right at you, then you were standing in the right place to begin with.' But my favourite might be this little bit of story-description from Lewis, who at one point observes that 'a phony debate soon heated up. It wasn't as interesting as a real debate, in that there was no chance for an exchange of ideas.'

We've all been there. And that's the thing. This book is about far more than baseball.

Based on the poster it seemed maybe this was going to be another epic seized upon for dazzling effects of destruction or rambling scenes of melodramatic heroism. There's a bit of that, but it's really just the set up for something more thoughtful. Rather than carelessly visualize the text (like that horrible Bible series--which I've actually warned my kids not to watch) this film digs into the particularities of the story and explores the themes both above and beneath the surface. All the right ones, in this case. It does take a few creative liberties but not, I think, to negative effect. Indeed, it gets to the heart of the text, with care.

Based on the poster it seemed maybe this was going to be another epic seized upon for dazzling effects of destruction or rambling scenes of melodramatic heroism. There's a bit of that, but it's really just the set up for something more thoughtful. Rather than carelessly visualize the text (like that horrible Bible series--which I've actually warned my kids not to watch) this film digs into the particularities of the story and explores the themes both above and beneath the surface. All the right ones, in this case. It does take a few creative liberties but not, I think, to negative effect. Indeed, it gets to the heart of the text, with care.

There was a hubbub amongst some anxiety-ridden opportunistic christian bloggers out there, but it really was all too much. This is a good, even great, film. But besides that, it definitely had an impact on me. When I saw it first with my friend and fellow pastor Micah we walked out at a loss for words, but later came back and found quite a few. I'm nervous about the Bible being ransacked for box office gains, but in this case the project gives much to be appreciated.

It turned out to have been a year for imaginative reflections on the story of the flood. This one made no pretensions to biblical accuracy at all, and indeed was the story of a dysfunctional family at the brink of an apocalyptic breech of worlds. The characters in this novel have all the social and psychological complexity of our contemporary neighbours, inhabiting a premodern world that feels like it could have been yesterday.

It turned out to have been a year for imaginative reflections on the story of the flood. This one made no pretensions to biblical accuracy at all, and indeed was the story of a dysfunctional family at the brink of an apocalyptic breech of worlds. The characters in this novel have all the social and psychological complexity of our contemporary neighbours, inhabiting a premodern world that feels like it could have been yesterday.

At times touching and at times frankly shocking, this is a story that gets you into the ark only after embedding you in a homestead with mythological proportions. Somehow the touch of fantasy adds scope to the most normal of family interactions, so that one enters the ark with a much fuller sense of the earthy humanity of the creatures who fill or fall outside of it.

My friend Nathan recommended this book to me, and once I was a couple chapters in I couldn't believe I hadn't heard of Timothy Findley before (least of all because he's Canadian). I've gone on to read some more of his stuff and some more good books besides, but this one really stuck with me. I recommend it. Just be ready for (spoiler alert) a flood story where Noah's the bad guy.

Sometime I might go back and re-arrange my lists to truly reflect my current opinion of the films--time changes memories, preferences, and even impact--but for now I'm leaving them as is. You'll find them in the tabs above.

I like a good list, mainly for the fun conversations they spawn. Thanks to all those who've talked about or recommended good movies or music or books with me this year, its these chats that usually bring the things to light and to life in the first place.

Album: Jason Isbell, Southeastern

Once I'd voiced my interest in country music only in the lyrically-rich and musically-creative vein of Ryan Adams and the Cardinals, my friends James and Tyler sent a few recommendations my way--including Dawes and, of course, Jason Isbell. This past year I listened to music mostly in my office and, whether I was emailing or writing sermons, Southeastern seemed to be on constant repeat. At times I would put it away for awhile and only come back to it with more conviction.

Once I'd voiced my interest in country music only in the lyrically-rich and musically-creative vein of Ryan Adams and the Cardinals, my friends James and Tyler sent a few recommendations my way--including Dawes and, of course, Jason Isbell. This past year I listened to music mostly in my office and, whether I was emailing or writing sermons, Southeastern seemed to be on constant repeat. At times I would put it away for awhile and only come back to it with more conviction.In the end it is Isbell's ability to be easy-going and earnest at once which I think draws me in, and of course the music is just excellent. 'Cover Me Up' and 'Live Oak' are tremendous songs, notable almost as much for their reserve as their richness (click a link and give it a listen while you read on). As the geographically-informed album title indicates, the storied-songs come from a place. It's a world I've never inhabited; nonetheless the songs hit home.

Book: Michael Lewis, Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game

Brad Pitt recommended this book to me (ha ha), and I'm glad I wasn't thrown off by the usual (well-warranted) worries that seeing the movie first would prove to have ruined the book. The film is very much about Oakland A's manager Billy Beane, but the book is also about the stat-keeping baseball hobbyists who stood behind Beane's revolutionary approach, and the marginalized players it came to benefit (and even save). What's so compelling about this story is how lovers of the game were able to set its profiteers on edge, and for a time almost take baseball back.

Most of my list of non-fiction books have to do with my area of study (theology), but this one belongs right there with them because of the complexity with which its human subjects are portrayed. These include not only Billy Beane but also Bill James, the stat-nerd behind sabermetrics, and Chad Bradford, the pitcher with the freaky-weird wind-up. What stuck with me the most, however, was the chapter on Scott Hatteberg, who said 'poor hitters make the best hitting coaches. They don't try to make you like them, because they sucked.'

Another memorable line comes from James, who says 'you have to do something right to get an error; even if the ball is hit right at you, then you were standing in the right place to begin with.' But my favourite might be this little bit of story-description from Lewis, who at one point observes that 'a phony debate soon heated up. It wasn't as interesting as a real debate, in that there was no chance for an exchange of ideas.'

We've all been there. And that's the thing. This book is about far more than baseball.

Film: Darren Aronofsky, Noah

Based on the poster it seemed maybe this was going to be another epic seized upon for dazzling effects of destruction or rambling scenes of melodramatic heroism. There's a bit of that, but it's really just the set up for something more thoughtful. Rather than carelessly visualize the text (like that horrible Bible series--which I've actually warned my kids not to watch) this film digs into the particularities of the story and explores the themes both above and beneath the surface. All the right ones, in this case. It does take a few creative liberties but not, I think, to negative effect. Indeed, it gets to the heart of the text, with care.

Based on the poster it seemed maybe this was going to be another epic seized upon for dazzling effects of destruction or rambling scenes of melodramatic heroism. There's a bit of that, but it's really just the set up for something more thoughtful. Rather than carelessly visualize the text (like that horrible Bible series--which I've actually warned my kids not to watch) this film digs into the particularities of the story and explores the themes both above and beneath the surface. All the right ones, in this case. It does take a few creative liberties but not, I think, to negative effect. Indeed, it gets to the heart of the text, with care.There was a hubbub amongst some anxiety-ridden opportunistic christian bloggers out there, but it really was all too much. This is a good, even great, film. But besides that, it definitely had an impact on me. When I saw it first with my friend and fellow pastor Micah we walked out at a loss for words, but later came back and found quite a few. I'm nervous about the Bible being ransacked for box office gains, but in this case the project gives much to be appreciated.

Novel: Timothy Findley, Not Wanted on the Voyage

It turned out to have been a year for imaginative reflections on the story of the flood. This one made no pretensions to biblical accuracy at all, and indeed was the story of a dysfunctional family at the brink of an apocalyptic breech of worlds. The characters in this novel have all the social and psychological complexity of our contemporary neighbours, inhabiting a premodern world that feels like it could have been yesterday.

It turned out to have been a year for imaginative reflections on the story of the flood. This one made no pretensions to biblical accuracy at all, and indeed was the story of a dysfunctional family at the brink of an apocalyptic breech of worlds. The characters in this novel have all the social and psychological complexity of our contemporary neighbours, inhabiting a premodern world that feels like it could have been yesterday.At times touching and at times frankly shocking, this is a story that gets you into the ark only after embedding you in a homestead with mythological proportions. Somehow the touch of fantasy adds scope to the most normal of family interactions, so that one enters the ark with a much fuller sense of the earthy humanity of the creatures who fill or fall outside of it.

My friend Nathan recommended this book to me, and once I was a couple chapters in I couldn't believe I hadn't heard of Timothy Findley before (least of all because he's Canadian). I've gone on to read some more of his stuff and some more good books besides, but this one really stuck with me. I recommend it. Just be ready for (spoiler alert) a flood story where Noah's the bad guy.